Marching monsters and the many faces of medieval grotesques

Like the stitches sewn into each shirt, comedic and crude monsters hide in the margins of illuminated manuscripts to weave a story into the gospels. And like stitches, the grotesques persist in their identifiability across the ages well into contemporary consciousness.

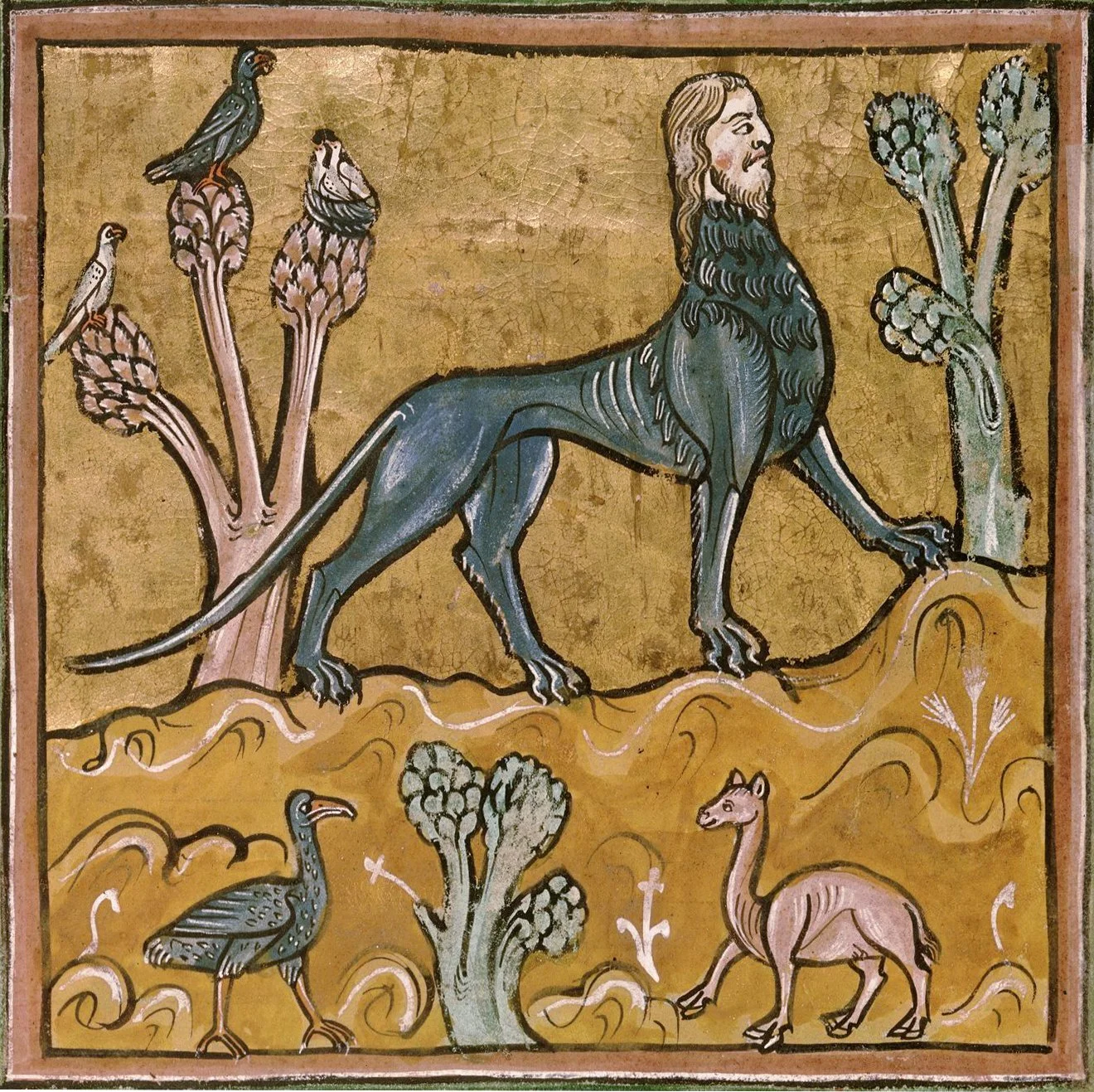

An illustration of a manticore, a creature with the body of a lion, the head of a man and the tail of a scorpion, from a 13th-century English bestiary.

I’ve long been fascinated by the evolution of medieval art, especially by the charming creatures dotting the many pages of manuscripts. With a full one thousand years' worth of history over a vast array of different cultures, every region and every century has unique artworks. The absurd monstrosities and cartoonish depictions of critters are just one of various recognizable staples of medieval history that cross the centuries.

In a quite motley assortment, bands of beasts are seen marching along the innumerable margins of devotional books between the 6th and 16th centuries. From the funerary procession honoring the humorous “Reynard the Fox” to the manticore’s cannibalistic feast, these painted illustrations were rarely a direct reference to the text they populated.

Folded into carefully crafted pages, such grotesques of dragons, harpies, headless men and delicate designs both crass and delightful instead served as decorative but meaningful supplements to ecclesiastical texts.

They were moral lessons and page numbers alike, reflecting human behavior and theological teachings throughout the books of hours, bestiaries and psalters ubiquitous with the period while marking a page’s proper placement in its folio.

Their proliferation is oft attributed to the efforts of the 64th Bishop of Rome, from 590 until his death on 12 March 604, Gregory I – the “Father of Christian Worship.” The patron saint of musicians and teachers, he emphatically promoted the use of illustrations in liturgical teaching by proclaiming, "What Scripture is to the educated, images are to the ignorant, who see through them what they must accept; they read in them what they cannot read in books.”

Thus, the liturgical books chanted in the halls of the monastery or taught to laypeople cultivated a thriving ecosystem of painted beasts. As the “literature of the laity,” according to the twelfth-century English scholar Honorious of Autun, these illustrations provided auxiliary material instruction for a largely illiterate population.

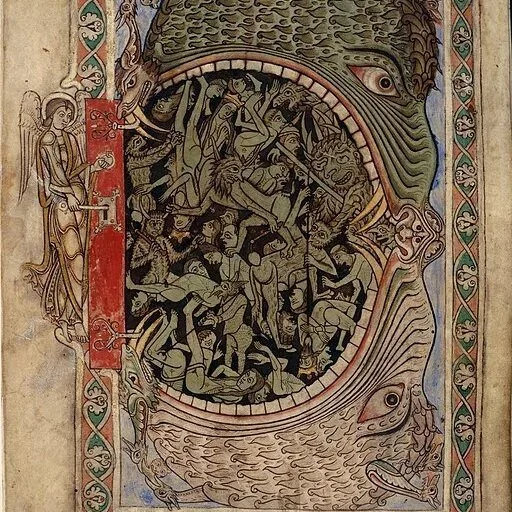

This 12th-century illustration from the St. Swithun Psalter/Winchester Psalter depicts the jaws of Hell, also known as a “Hellmouth.”

Consider the “Hellmouth,” a commonplace image dancing throughout each century of the millennium. In most depictions, it imagines the gate to Hell as the gaping maw of a great monster, salivating as it swallows whole the nude damned and un-resurrected unfortunates during the end times.

The most harrowing image served as the most dire and uncompromising reminder to the medieval penitent of the punishment that awaited the unworthy sinner at the end of days. And yet, while each brushstroke shouldered the weight of religious dogma, they also served as outlets for creativity and political critique in a period and region lacking in the freedom of expression.

We have gleaned from many manuscripts, the beasts were not all so monstrous. Others were humorous, perhaps grimly so. Reynard the Fox, for instance, was popular across the millennium both as a trickster fairy tale and a social commentary of the various ruling institutions of the time. Of the trickster archetype, a vast array of tales depict Reynard as deceptive, intelligent and humorous. One popular image across the ages portrays him as a deceptive priest, preaching before an audience of gullible birds whom he intends to devour. Soon, they would hear not the horns of heaven’s angels, but that of their own flesh tearing in Reynard’s jaws.

Reynard the Fox preaches to a variety of fowl, soon to be devoured.

Though in other tales, you might find him to be a sympathetic antagonist, a champion of the peasant – whose sly wit was born out of necessity to survive in a world that pushes against him at every turn. In many stories, Reynard’s motivator is hunger, born from a starvation and lust for that which he cannot have. He wants for the meat that lords freely fill their bellies with, the meat forbidden to their peasants despite the way it proliferates their forests in an ever present temptation. He devours without fear, knowing only execution awaits.

God with Adam and Eve The First Rain in Paradise, around 1200 - 1254

Manuscripts and the illustrations within were a learned man’s dictionaries - naming the animals like Adam. They were a servant’s tributes - embellished with rich gold leafing and vibrant paints. They were a penitent’s vesper in the evening - safe from the sin of idolatry by defining the cross not as the object of worship, but as a tearful devotion to the human lying dead upon it. Consequently, depictions of the passion are paid special attention to imbue piety in the brush strokes making up the Lord’s bloody and broken body. They tug at the sinner’s heartstrings, evoking empathy and admiration for the pain and death of the savior, calling at them to repent their transgressions to the almighty church. They encourage contemplation, to sit alongside the gruesome and holy crucifixion, bleeding red ink into the pages. Understanding the ecclesiastical lessons was but one step closer to understanding God’s will, as the Father of Christian Worship so proclaimed.

But, with each devotional text, the reader glimpses the monsters lurking in the margins, sees the priestly Reynard the Fox lick his lips toward unsuspecting prey fit for the slaughter; a grim reminder that even God’s own church can abuse them.

It’s a tale as old as authority itself, and it’s a method as old as commentary that we use art to satirize structures of the time.

We are fortunate the preservation of illuminated manuscripts has guaranteed such stories can remain ever-present and ever relevant.

Even centuries later, Reynard the Fox is still illustrated, as seen in this 19th-century depiction by Wilhelm von Kaulbach.

As this is my first written blog, I recognize that it may be unpolished around the edges. I still hope you found this an enjoyable read. There's a thousand years of art history that I can only begin to touch on in these posts, the short writings you’ll find in Folds in the Folio are only a drop of ink on an otherwise infinite manuscript.

Regardless, thanks for reading this far. Next, I'd like to dig into the ink used in the manuscripts themselves. Since the medium is just as important as the content in any piece of art, I think it can help provide context for the other topics I'll be writing about.