Gall, gum, vitriol and the making of medieval black ink

Bound in leather, bathed in ink, each manuscript was a child painstakingly born from the sweat and devotion of its author. There is an intimacy in the manuscript, with scribes devoting hours upon days, days upon years and years upon lifetimes in quiet preparation of the folio.

While a manuscript is produced by the human hand of its scribe, there is another parent to the manuscript: The buzzing of a stray insect and the plucking of a growth from a tree for its transubstantiation into a rich, dark ink.

Imagine gripping in your hand the woody growth of the gall, admiring each imperfection across its rough, nutty surface.

It is from this nut that, bruised as it is, vast annals of culture, both fact and fiction, would be recorded for your peers and those who will follow behind you.

For any medieval scribe, the making of black ink was as important as its use. To understand their materials and the manuscripts to come from it, the artist relied on their surroundings, using local materials found in nature and the aid of trade and apothecaries to marry mineral and pigment into the tool by which they would illuminate.

Black ink, as with much of medieval culture, adhered to a trinity: Gall, gum, and vitriol – or iron.

The text from this 1270 manuscript remains legible.

Throughout the Middle Ages, the black ink of scribes’ iron-gall dominated the greatest ocean of manuscripts. Commonly made from forms of iron salts, gum arabic, and gallnuts, diseased growths on the oak tree bred from wasp eggs, gall ink soaked thousands upon thousands of pages in the most delicate of calligraphies.

It is with the sunken stones of wasp eggs that we can still glean from centuries-dead authors their most private histories.

To make it, scribes plucked from oak trees their beautiful freaks of nature, galls, and soaked them in water or wine, stirred over two weeks with iron sulfate to form a rich black with which they would bleed into parchment. The addition of gum binded the pigment, letting the ink flow like a rich, dark wine and adhere to parchment.

Unfortunately, like many beautiful things, gall ink will fade with time. It sits upon parchment, impatiently waiting its turn to leave its manuscript behind. What we’re left with are the faded brown lettering found across manuscripts. But there are other forms of inks, some made from walnuts (generally used for drawing), carbon or tannin, a compound found in plants. But the black ink’s so well-preserved text after centuries of neglect remains a recognizable witness to the recipe’s prevalence well into the 19th and even 20th centuries.

We’re fortunate, then, that even the most fading of gall-inks persist into our time as fruit for investigation. X-ray Fluorescence spectrometry (XRF) is a non-destructive method by which we can investigate even the most hidden properties of inks, and see what remains.

If you know me, you might be aware that I had a career related to physics and the study of light. While poring over the many journal articles required in my line of work, I developed an interest in imaging, particularly in its usage related to artwork.

Optical imaging, by which many old artworks are studied, refers to leveraging light across the entire spectrum, and its properties create images. X-rays are also used to capture imaging, but rely on radiation to do so, and can peer through layers, like skin and parchment.

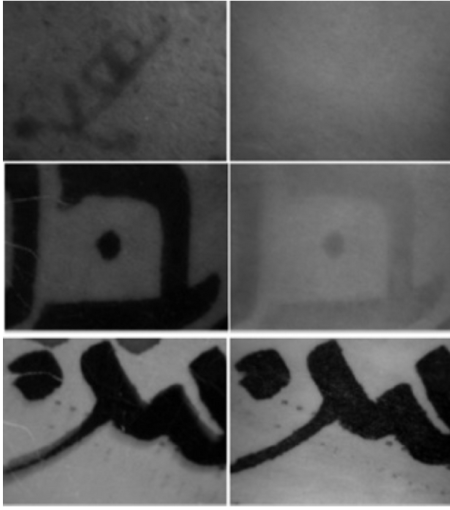

See here, in a chapter of Material Studies of Historic Inks from Ira Rabin, a series of letters drawn in varying inks: Tannin, iron-gall, and carbon. On the left, we are treated to a manuscript imaged with visible light. On the right, we can ponder the same manuscript, imaged with near-infrared (NIR) light. From the top of the ladder down, these letters are written in tannin, iron-gall, and finally carbon ink.

Relying on XRF, we can not only characterize ink itself, but also how it was wielded by its author.

The medieval period, despite a contemporary tendency to characterize it as a backwards period of strife, bloodshed, and cultural ignorance, was rich in cultural exchange. The Silk Road provided ample opportunity for the exchange of techniques and materials. Just as trade exchanged goods, trade also shared the love of inkmaking from scribe to scribe.

Arabic recipes, especially those featured in manuscripts, often showcased harmonious blends of various ingredients. Gum arabic, one of the ingredients in the trinity of inks, was generally imported from Asia Minor.

The left-behind chemical remains of ink long since dried, the balance of copper to iron or zinc to iron, and the harmonious blend of materials – perhaps multiple inks fused as one: another trinity at which manuscripts followed subconsciously to its author’s intent.

And with art’s reflection of its artist’s inner secrets, perhaps it's only poetic that we’re invading the privacy of long-forgotten scribes. As craftsman, they so jealously guarded their secrets, not only the recipes behind black ink, but behind the decorative pigments around it.

Reds, blues, greens, pigments of all shades, craftsmen held each decoration associated with the illuminated manuscript close to their beating hearts. Fortunately, some among them were generous enough to provide us with the secret recipe. One such recipe, housed in the University of Cambridge’s library, is as follows:

“To make gode blak yngk as ony ys in Ynglond. Take an vnce [ounce] of gallys, an vnce of gume, and an vnce of grene coperose, brose [crush] all thyse togeder almost to pouder and put hit in a pott … than put therto a pynte of rayne water or of stondyng water that rynneth nott, than stere [stir] hyt euery daye and within .iii. dayis ye schall have gode yng”

The works of Chaucer, the recording of Beowulf, songs and stories of people long past yet walk alongside us, with thanks to the natural efforts of the gallnut, some gum and a bit of vitriol.